The Desires of the 'Weird Girl': Burn (2019) & Dinner in America (2020)

Female perverts unite (?)

*Content warning: Burn includes a rape scene, which is discussed below. Please read with care!

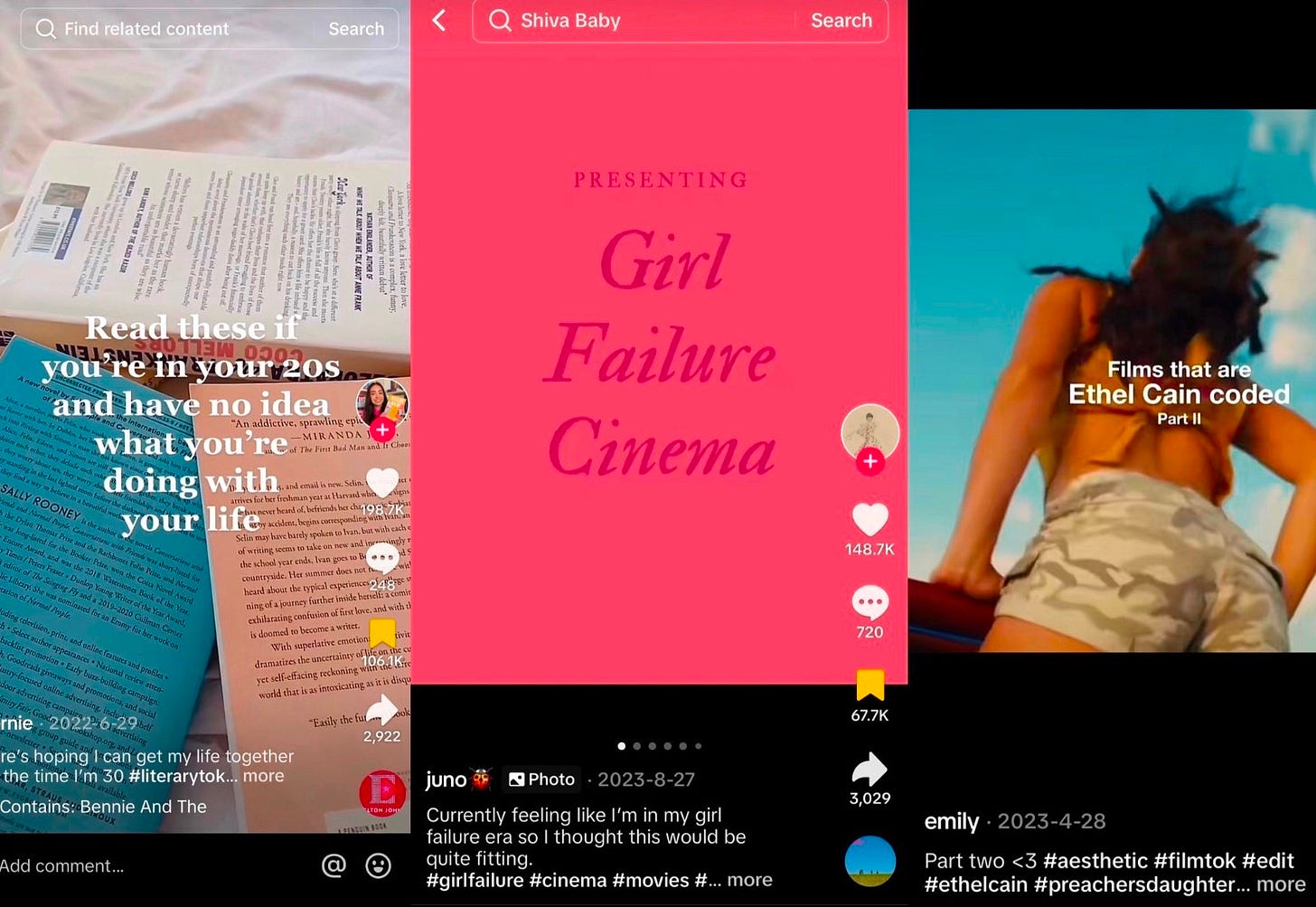

I’ll be the first to admit (without shame, by the way) that I get the occasional music, book, and movie recommendations from TikTok. It doesn’t mean that they’re always good–there’s more than one book I’ve skimmed at the library before putting it back on the shelf with little remorse–but it also doesn’t mean that they’re bad, either. At a base level, it’s interesting to take note of what other people are listening to, reading, and watching–especially when it seems that a lot of people are listening to, reading, and watching something all at once. There are a lot of listicle type TikToks in my favorites folder, with intros like “books for when you’re a young woman, lost in your twenties” and “weird girl cinema”. When I’m really stuck on the Netflix/Hulu/Max/Prime (etc etc etc) carousel, I’ll often peruse these recommendations and pick something, the more impulsive the better.

If you’re on the film/bubble-grunge/‘weird girl’ (heavy air quotes here) side of TikTok, you’ve probably seen a few (or more) videos praising Dinner in America. Released in 2022 after premiering at Sundance in 2020, the film follows Simon (Kyle Gallner, of Jennifer’s Body fame) and Patty (Emily Skeggs, of Fun Home fame) as their lives intersect in vaguely 1980s suburban Michigan. Simon, a pyromaniac slash punk rocker, wanders aimlessly and angrily through other people’s families, setting fire to lawns and selling drugs. Attracting police attention, he seeks refuge with Patty, a recently-fired pet store employee and community college drop out, after a chance encounter in an alley. Things go from there–the plot is character driven, for the most part, with the movie spending almost the entirety of its 108 minute runtime on the relationship between Simon and Patty.

I watched a lot of it with a smile on my face. Dinner in America is well written, acted, edited, and directed. It’s just well put together–it’s funny, and memorable. I’m writing about it because I’m still thinking about it. I watched it after bailing on I Used to be Funny after about seven minutes of runtime (which is unusual for me, noted masochist, but I didn’t have a great feeling about dialogue that was so stiff it made Caleb Hearon fall flat), and I was completely refreshed. It reminds me of other ambitious movies, playing off John Hughes archetypes while adding surrealistic sequences of violence (2019’s less successful Riot Girls comes to mind). But where this kind of movie often falls short, Dinner in America seems to understand its limitations, and fills every crevice of its relatively small cast and locations.

All of these things are why the movie is have a second wind on TikTok, years after its general release–but perhaps what’s being talked about the most is Patty, and her ‘weird girl’ representation. Patty from the start of the movie to the end, is frank, awkward, and at times, unsettling, albeit in a lighthearted way. She is also a sexual being, and her sexual desires play a clear and important part in the movie. In one of our earliest scenes with Patty, we get a sense of who she really is outside of her job and family dinners as she her dances around her room to rock music, before furiously masturbating and taking a Polaroid of herself at climax. Her sexuality is a device to show us who she is; the audience does not gain sexual satisfaction, but rather an understanding of Patty as a character.

It’s unsurprising that Patty resonates so hard with a female audience. In the girl-boss, weaponization-of-femininity world of the 2010s, blockbuster films worked hard at trying to convince women that writing scantily-clad female characters who desired sex in–surprise surprise–the exact same way as the average male fantasy, was feminism, actually. Post Joss Whedon’s Avengers, it’s incredibly refreshing to showcase female desire that doesn’t exist to solely turn the viewer on. Patty’s desires are presented to us, and then we get the joy of those desires being fulfilled, without compromise. Patty grows throughout the movie, but not into a person that is more palatable or acceptable to her world–or ours. In fact, by the end, she is less accepted by the status quo, and happier for it, only slightly tweaking her outward appearance to be what we can only guess is a truer representation of her inner self.

Reflecting on Dinner in America and its focus on frank female sexuality brought to mind another film–2019’s Burn, starring Tilda Cobham-Hervey, Suki Waterhouse, and Josh Hutcherson. In Burn, a stick up at a suburban gas station goes horribly off the rails, resulting in multiple deaths and, as the title would suggest, a fairly spectacular explosion. Our protagonist is Melinda (Tilda Cobham-Hervey), a graveyard shift employee of the gas station being held up by Billy (Josh Hutcherson), a would-be robber with a short fuse and exceptionally prone to violence.

Burn is a thriller, starkly different to Dinner in America in many ways. In Dinner in America, against all odds, things manage to go right for our protagonists. Burn, in contrast, plays out a scenario in which something that should have been so easy goes utterly wrong. But before Billy ever wanders onto the scene, we spend some time with Melinda as she arrives at work and starts her shift. Like Patty, she is our ‘weird girl’–awkward and off putting. As we follow her around her various tasks at the gas station, we witness her attempts at flirtation with customers, failing every time. Unlike Patty, who feels more authentic than her plasticine suburb, Melinda’s multiple failed would-be sexual displays read as artificial. Not because she doesn’t want them, but because they are clearly the desperate product of intense loneliness and a clear inability to connect to her outside world. Patty seems disconnected because her setting is limited; Melinda’s disconnect is a skill issue. It’s no surprise then, that she attempts to leave the gas station with Billy in return for the money in the safe, just as it’s no surprise that he refuses her. She has chosen a poor partner in crime, and the results of her unrealized sexual desire result in a world burned to the ground.

It’s clear from the start of the movie that while Melinda is our protagonist, she’s also something of a ‘femcel’; an interesting example of an incel turned on its head. She is so desperate for intimacy that she will proposition anyone, up to and including the man robbing her at gunpoint. And her continued rejections lead to very dark places. In an incredibly difficult scene to watch, Melinda attempts to rape a tied up Billy. She is largely unsuccessful, and as the plot progresses, we see her react with horror to her actions, turning the gun on herself and almost taking her own life in front of customer who is blithely unaware of the greater plot. Understanding that she has done several awful things, resulting in the death of her coworker, and it's all on camera, Melinda is pushed to desperation to destroy all evidence, including Billy. And at the end of the movie, Melinda ostensibly gets what she wants–the gas station is destroyed, along with the security camera, and Billy is dead. Perhaps more importantly, she has captured the care, if not the romantic attention, of her crush, a police officer who frequents the gas station.

Melinda is an interesting character to examine, especially in contrast to a character like Patty. Whereas there feels like a tender care with how Patty is written, it’s easy to look at Melinda and see the age-old trope of the neurodivergent individual played for cheap thrills, at the damaging expense of a real community. On the other hand, I think it’s also possible to view Melinda as a representative of incels in general, with her gender being what makes it possible to observe from a distance. Her sexual desires cloud her judgement and reduce people to objects. Burn is not trying to completely alienate her from us–she is still our protagonist, even after her horrifying actions– rather, I think that it is creating an extreme environment as representation of her dissatisfaction, and then lets the cards fall where they may, while we sit in discomfort. I think its safe to say that when people can’t access intimacy with others–emotional, sexual, or otherwise–what tends to come out of them can be intense.

To be clear–if you’re going to watch one of these movies, watch Dinner in America, for the simple reason that it is a better project. I get the impression that I credit Burn more than the average viewer, but it’s undeniable that it’s missing something to make it truly good. Both of these movies have a lot in common–they heavily feature sexual longing and violence. They both have small casts and a contained world with limited locations. Both movies explore decay in American suburbia. The main difference (in quality, at least) is execution and humor. It’s very possible that Dinner in America, played totally straight, would stumble, and Burn, played as a dark comedy, could really shine.

All that being said, be it thriller or rom-com (if you could call Dinner in America a rom-com), well executed or not, I’m always intrigued when we get a female character that exists outside of the male or female gaze (regardless of whether or not such a thing as a ‘female gaze’ can exist when applied to female characters, being that any presentation-based expectations we have for women are extensions of the patriarchal eye). We (and I mean everyone, not just women) deserve female characters that are allowed to be at odds with the expectations of the world around them. Patty is a character both new to the screen and yet completely familiar, in the sense that her interior world is familiar. Female sexuality may be relatively new in media, but women have always known of its existence. Every time we get a character like Patty, it feels like an acknowledgement of what’s always been true–that women have their own desires, completely separate from the state-sanctioned, appealingly sanitized and packaged for male consumption, idea of them.

And, when presented with care, it makes intimacy between characters all the more believable. There’s a beautiful moment in Dinner in America where, in the basement-turned-music-studio of Simon’s childhood mansion, Patty sings the song she’d previously written for John Q., possibly over a year ago. Tears welling in his eyes, Simon gazes at Patty with what can only be described as adulation. Watching it, I could only think of the Hao Miyazaki quote, about creating protagonists who mutually inspire each other to live. I think the moment was something slightly more than that, if even possible–Simon and Patty look at each other and realize that not only have they loved each other before they ever met, but that somehow, incredibly, the person in front of them is living up to the fantasy of who they created to wade through the monotony of the dissatisfaction of their everyday lives. By showing us the specificity of these people exactly as who they are, whether or not they are palatable to the world around them (and they aren’t, as displayed multiple times throughout the movie) it allows us to access a world of total, radical acceptance giving way to earnest admiration and yes, love.